Yet another introduction to LaTeX

07 October 2017

If you’re reading this, you probably know what LaTeX is roughly. LaTeX works by first separating the content and layout of the document. The user can then specify the layout parameters and any design they choose. LaTeX is then used to create the final document, constraining the content to the design parameters.

Since the document is produced

This introduction is not so much about creating LaTeX documents, but an attempt to show how the structure of a LaTeX file relates to the document it produces

The structure of a document

Dimensions

Lets start off with a page from a book. When you first look at piece of page, the first shape you see is a rectangle formed by the edges of the paper. The next largest shape is the rectangle that the body text is constrained to. If there is margin text, that too is constrained to a rectangle that doesn’t overlap with the body text. Perhaps there could be more rectangles defining tables, images, quotes, and so on.

Typically, these rectangles will lie wholly inside another, and do not partially overlap with another rectangle. There are various quantities that define the distance between one rectangle from another. Most notably, the margins define the closest the content can be to the edge of the paper. Similarly, there will be a distance seperating margin notes from the body text, images from the body text, the distance between chapter headings and the text… there are a lot of distances. Infact, the rectangle you need is the paper size, the rest of the structure and be define by these distances.

Text Structure

Of course, books aren’t the only kind of document in existence. Reports are not necessarily double sided, nor are they always bound like a book. They also are shorter than books, and thus don’t need headings larger than a chapter. On the other end of the spectrum, a letter can be as small as one page, and generally consists of three items: the senders address, the recipients address, and the message. The text formatting also differs, with books most likely using single spacing, while letters and reports can be found using larger spacing between lines.

The result is that each type document type has a different set of rules on how to display text. The rules should applied uniformly for every part/chapter/section/caption. They contain information such as font size, alignment, numbering, padding from surrounding text, and so on. Some rules will be enforced rigorously, like font colour, and others not so rigorously, such as the spacing between words.

If you are familiar with CSS, the styles you define are essentially the same as these rules, except the page boundaries are far more varied in ratios and scale.

Put together

Creating a document is then done associating each bit of content with some rule, then piecing together each bit of content. This process is analogous to the combination of HTML and CSS, where HTML defines the structure of the webpage and provides some bare essential rules to piece together the content, and CSS provides more fine tuning and does the real styling of the page.

The document as a LaTeX file

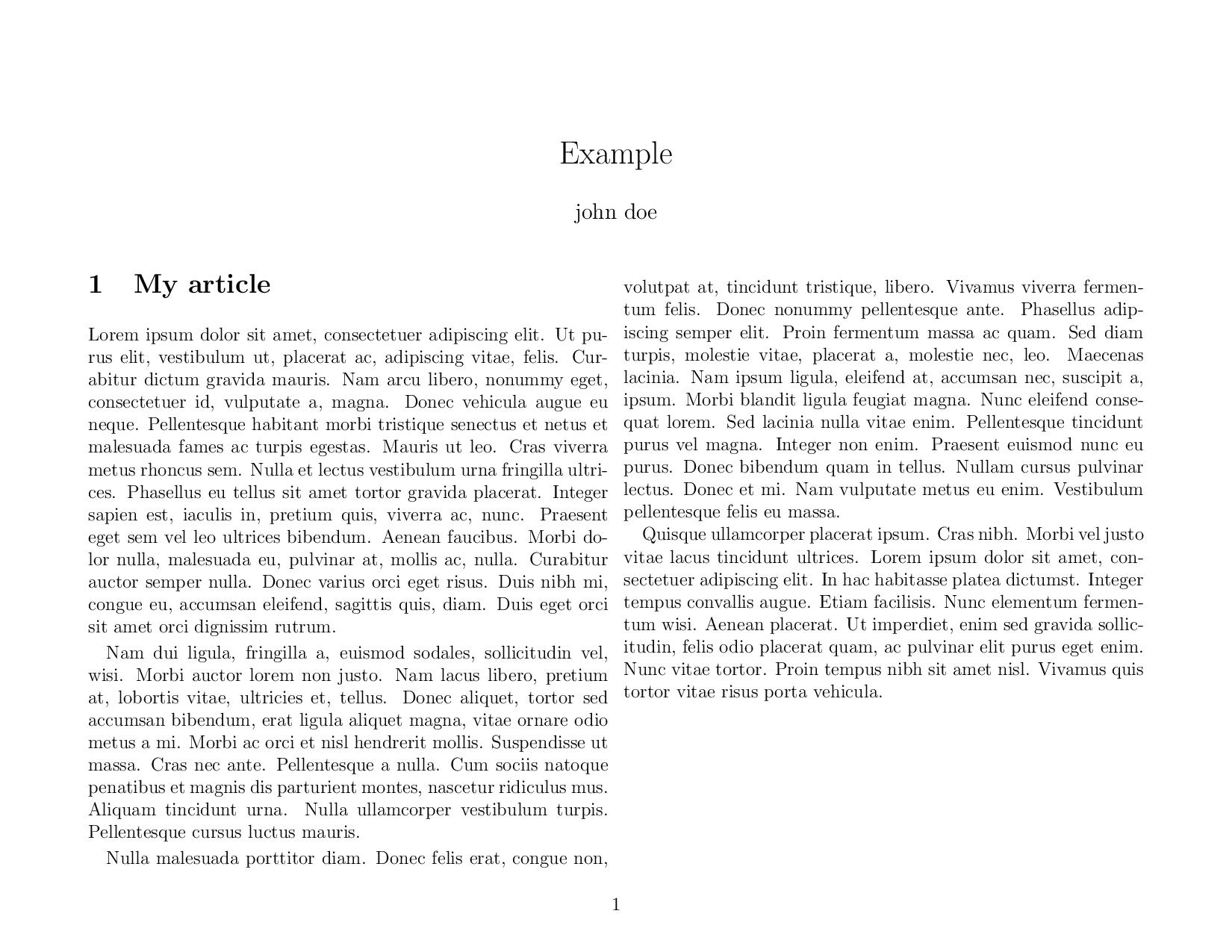

Here, we will go through the process of making a simple article, with some customisation to illustrate how change rules. This is page we will make:

Globally defined rules

There are some rules you can safely design for an entire document. Examples include the typeface you want for the body text, or the paper size. Essentially, these are default rules, since they can be changed mid-document. In a LaTeX file, these are given in what is called the preamble. The preamble is special place where you can define the default rules for the entire document.

Lets start off declaring that this document is to be an of an article type. Firstly, we need the type of document we are making. This can be done with the code:

\documentclass{article}article is a name for a particle style of article, but it is not the only type. KOMA-script has its own analogues for book/article etc such as scrbook.

Next, we need to make the article in landscape, with two columns. It is possible to use pure LaTeX, or TeX, to add these rules, however other useful people have done the coding already. The useful bits of code can be included by introducing packages. The first such package is the geometry package, which gives lot of useful tools for changing page dimensions. Lets include it:

\usepackage[landscape]{geometry}The \usepackage command tells latex use the package in the braces (geometry), while in the square brackets you can specify some options that will set some rules, which in this case is set the page to landscape. Package are included in the distributions you download, so it should work without any fiddling.

To force it landscape, we add an argument to \documentclass. While we’re adding arguments, the font size can also be specified here (perhaps confusingly):

\documentclass[12pt, twocolumn]{article}Lastly, we get some dummy text we can use the lipsum package. All it does is that it gives a command to generate dummy text in latin.

\usepackage{lipsum}The end result for the preamble is:

\documentclass[12pt, twocolumn]{article}

\usepackage[landscape, margin=2cm]{geometry}

\usepackage{lipsum}Remember these define rules for the content, and provide some utility in the form of extra text. They do not constitute the content by itself. The next we need to do is add some content.

Environments

Say you have a quote, and you want to have it styled using a different set of rules. Generally to this, you need to provide two things: the name for the rules to use, and where to place these rules. In LaTeX, when you provide both of these you are using an environment, and it has the form:

\begin{environment_name}

%put stuff here

\end{environment_name}Any content between these statements will have the rules define by environment_name. An example could be bullet pointed list, which looks like

\begin{itemize}

\item item 1

\item item 2

\end{itemize}The \item command becomes available in the itemize, and most if not all list-type environments. It tells LaTeX what this is a list item, so format it according to the itemize rules which simply adds a bullet point to the front of the text.

This comes up everywhere in LaTeX, so you will quickly become acquainted with it.

Content

So now we’re at a point where to want to specify the content. This is easy, all was need is the document environment, which contains all of the rules in the preamble.

\documentclass[12pt, twocolumn]{article}

\usepackage[landscape, margin=2cm]{geometry}

\usepackage{lipsum}

\begin{document}

\lipsum

\end{document}Here, the \lipsum is from the lipsum package, and all it does it create some dummy text. You should be able to compile this, and find the pdf is missing two things: the title, and the section heading “my article”.

All content lives inside the document environment, including the title information. LaTeX provides some easy commands to do this:

\title{Example}

\author{john doe}

\date{}

\maketitleThe commands are self explanatory, except the \date{} line which has no content. This just removes the date from the title, or you can add a set date inside the brace, or use \today for todays date. \maketitle tells LaTeX exactly that, make the title! If you don’t include it, the title won’t work.

Lastly, we add a section header. LaTeX provides a set of headers, which you can find easily here. In this example I simply use \section{My article}. The final result is

\documentclass[12pt, twocolumn]{article}

\usepackage[landscape, margin=2cm]{geometry}

\usepackage{lipsum}

\begin{document}

\title{Example}

\author{john doe}

\date{}

\maketitle

\section{My article}

\lipsum[2-4]

\end{document}Note that some commands can also take arguments, as can be seem by the \lipsum[2-4] line. This tells the \lipsum command to produce command from paragraphs 2 to 4, which makes the document one page.

Conclusion

LaTeX may be intimidating at first, especially if you never done any programming or markup before. But I find its useful to remember that what you are really doing is defining rules for the content. The hard part is finding how to implement some of these rules, either by yourself or with the help of packages. When I need to find some relatively simple LaTeX command, I jump straight to LaTeX wikibook. When I something a bit more, I just google what I need. This typically leads me to a StackExchange page where someone else has asked exactly the same question.